I’ve written a bit here about how I came up with the idea to write about three friends who are all governesses and each find their happily ever after in their own time. What I haven’t talked about is why governesses? The answer is simple: governesses occupied a fascinating space as educated, well-bred ladies who earned a wage but weren’t servants. That status on the fringes of society makes them all the more interesting to write about.

Who Was the Victorian Governess?

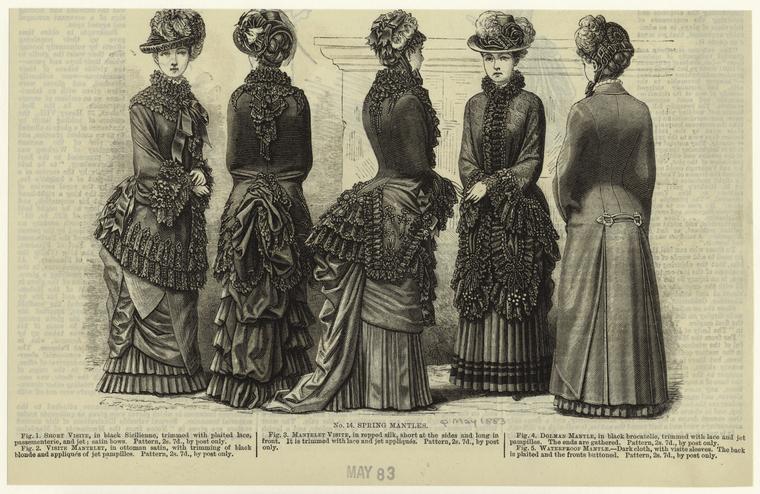

If you’re only vaguely familiar with who governesses were and what they did, here’s a primer. They were often educated, respectable women who’d fallen on hard times, the daughters of parents who couldn’t afford to keep them at home until they married, or other down-on-their-luck widows armed with a good reputation. These women could make an income by educating the girls of a well-to-do middle- or upper-class families until their charges were married and became the mistresses of their own households.

And intentionally or not, governesses were subversive as hell.

It’s important to remember the context of the time period we’re dealing with here. During Victorian England society was governed by a phenomenon called “the two spheres.”

Convention dictated that men occupied the public sphere and could go off into the world and do things like manage businesses, enter into politics, or work. Women got to stay at home.

“The prevailing ideology regarded the house as a haven, a private domain as opposed to the public sphere of commerce,” writes Elizabeth Langland in her article, “Nobody’s Angels: Domestic Ideology and Middle-Class Women in the Victorian Novel."

White, straight, cisgender women of the middle and upper classes occupied this “private sphere,” but at the same time their money allowed them to delegate many of the duties that would have traditionally fallen to women. In households that could afford it, you hired a maid-of-all-work, or if you had more money specialized servants like chamber maids, ladies maids, and a cook. Families who could afford it hired a nurse and, for the education of their young girls, a governess.

The Governess as a Sexual Threat

Governesses, by professional necessity, were not married. They lived in their employer’s homes and therefore had an intimate knowledge of a family regardless of whether their actual relationships with the individual members were warm or not.

Even though governesses were a status symbol of a certain degree of wealth and class, they were still looked on with suspicion. Having an unmarried woman in close proximity to a husband or older sons was seen as a direct threat to domestic peace. The historian M. Jeanne Peterson quotes at length from Mary Atkinson Maurice's Governess Life (1849) in her article “The Victorian Governess: Status Incongruence in Family and Society:”

Frightful instances have been discovered in which she, to which the care of the young has been entrusted, instead of guarding their minds in innocence and purity has become the corruptor—she has been the first to lead and to initiate into sin, to suggest and carry on intrigues, and finally to be the instrument of destroying the peace of families…

Because the governess wasn’t the “traditional” Victorian woman who stayed within the confines of her own home and therefore the private sphere, she was seen as threatening to the very structure that held society in check.

Even more concerning — and surely ridiculous to modern readers — was that Victorian womanhood was wrapped up the idea that the ideal woman was modest and retiring when it came to sex. The accepted model of female sexuality can be most easily seen in the works of the much quoted and undeniably naive Dr. William Acton who believed that that “the majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled by sexual feelings of any kind" (The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs, 1857). If a woman lived outside of the bounds of her traditional role, she must be a threatening, oversexualized figure. This is where the governess-as-seducer trope you see with characters like Vanity Fair's Becky Sharpe gets its bite.

The Governess and The Economic Threat

Governesses didn't just offend society's ideas about womanhood because of they lived close to men or their perceived sexuality. They subverted strictly gender roles for middle-class women by earning a wage. This gave the governess access to money, economic independence, and choice — all hallmarks of what we would later come to know as feminism.

Woman in Victorian England had little say over their own money. It wouldn’t be until a series of Married Women’s Property Acts* increased the legal rights of women under British law throughout the 1800s that a woman could inherit and maintain control over her own money within her marriage. Before then she was essentially beholden to first her father and then her husband and sons for the duration of her life. She was essentially a charity case who had little legal recourse if the man who was supposed to be providing for her was instead frittering away her money.

By living outside of the traditional father-daughter or husband-wife structure and earning her own wage, a governess could exercise a degree of independence by having power over her money.

I don't want to paint too rosy a picture for the Victorian governess. She didn't earn much money so the independence she did have was limited. “Her working life was not likely to last more than 25 years, at a starting salary of 25l, rarely reaching 80l” (Liza Picard, Victorian London: The Tale of a City, 1840-1870, p. 262).

While teaching was one of the few respectable ways for a middle-class woman to earn her living,** the governess was relegated to a lower social status than her charges. Still, she was earning money and was beholden to no man which meant she had legal control over her income — something married women couldn't boast of until well into the 19th century.

Making Them Heroines

The conflict built into the governess's life — whether it's the perceived threat to the fidelity of a marriage or her uncomfortable limbo between lady and servant — makes her the perfect romance heroine. There's conflict built into her story from page one because she doesn't fit neatly into the boxes that Victorian society assigned women. No matter who the hero (or heroine in the case of F/F) is, there is going to be a tension regarding her non-traditional role in the home and in society. And great romance comes out of great tension.

*You can read more about these acts in Mary Lyndon Shanley’s Feminism, Marriage, and Law in Victorian England, a dry but fascinating book.

**Another was writing. Mary Wollstonecraft and Frances Milton Trollope were just two of the women who picked up their pens to earn money during the Georgian and Victorian eras.

Further Reading

Feminism, Marriage, and Law in Victorian England, Mary Lyndon Shanley

“Nobody’s Angels: Domestic Ideology and Middle-Class Women in the Victorian Novel," Elizabeth Langland

“The Victorian Governess: Status Incongruence in Family and Society," M. Jeanne Peterson

“Victorian Sexualities,” Holly Furneaux

The Mystery of Princess Louise, by Lucinda Hawksley

The Mystery of Princess Louise, by Lucinda Hawksley

!["Blackwell's Durham Fashion Doll [paper doll with dress]" Courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections.](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ad35ac8372b96bedc6d2d6e/5adcdc8e680cc374b9599d86/5adcdd54680cc374b959b489/1524424020591/nypl.digitalcollections.510d47e3-d99f-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.001.w.jpg?format=original)

05.jpg/220px-James_Barry_(surgeon)05.jpg)

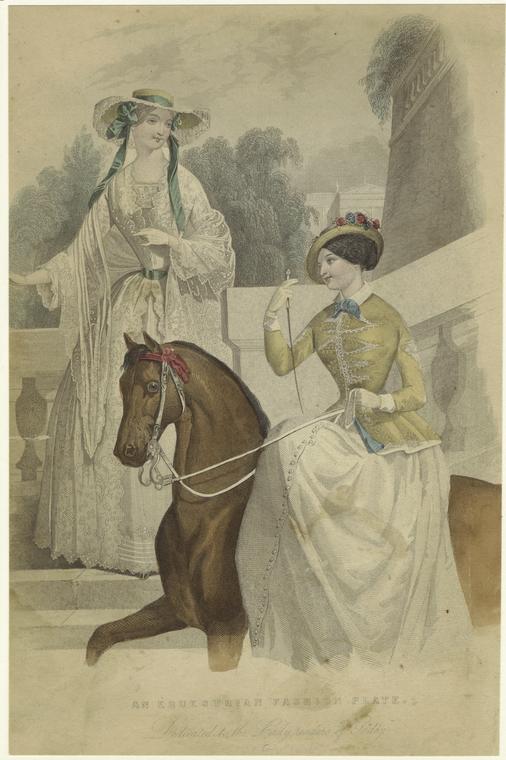

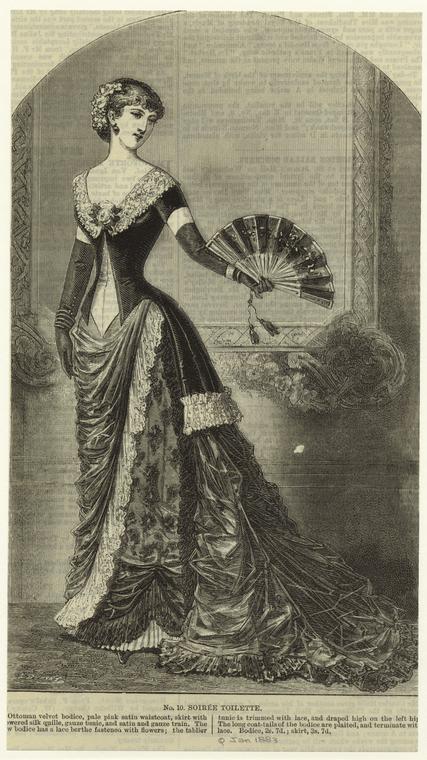

This Sunday was Marathon Day here in NYC. I, like many New Yorkers, live right near the route. While I love the marathon, sometimes the crowds can get a little rough. This year I cheered on some of the runners earlier in the day and then left the neighborhood to do something I never do. Dear Reader, I went to the Met on a Sunday and took a boatload of photographs.

This Sunday was Marathon Day here in NYC. I, like many New Yorkers, live right near the route. While I love the marathon, sometimes the crowds can get a little rough. This year I cheered on some of the runners earlier in the day and then left the neighborhood to do something I never do. Dear Reader, I went to the Met on a Sunday and took a boatload of photographs.