I love historical fashion from pantaloons to pelisses, and over the years more and more of it has made its way into my books. Clothing can be a wonderful way to ground a scene in a time and place, and it can also tell you a lot about a character.

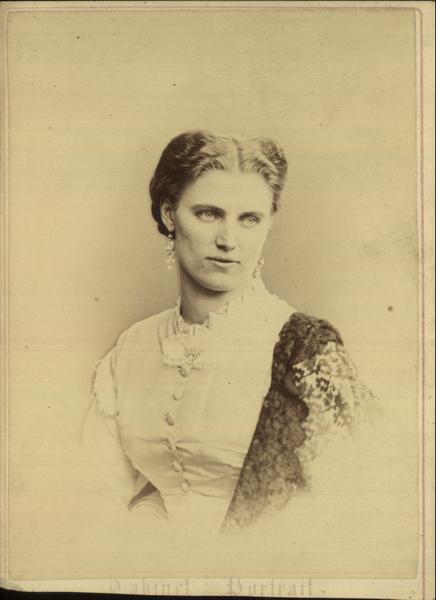

When I started writing Elizabeth Porter, the heroine at the center of The Governess Was Wicked, I knew I'd set myself a particular challenge. Governesses typically wore simple clothing in a limited range of colors (think functional colors like greys and dark blues and greens) and with few embellishments. She would have had a few dresses including her "best" dress that would have been worn to church or on special occasions. Otherwise, her clothing would have had to last as long as possible to maximize on cost.

Most of what we see in museums are beautiful examples of exquisite — and exquisitely expensive — gowns. The more workman-like dresses weren't necessarily preserved for history. That means that you'll see a lot more of Mrs. Norton's wardrobe when you go to museums than you will Elizabeth's.

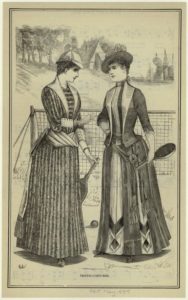

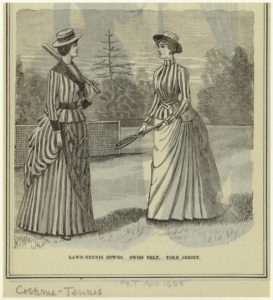

While her clothing might not have been as luxurious and fashion-forward as the woman whose children she educated, a governess did share something in common with her mistress: they both wore the same silhouette.

The late 1850s was characterized by large, bell-shaped skirts that flared out from a tightly cinched waist. One big development in undergarments allowed women to achieve these huge skirts: the cage crinoline. Up until this point, ladies would have piled on petticoats to create a full effect. Although they look horribly impractical to us, crinolines of wire covered with cotton actually created a structure for a dress to lay on top of and flare out from the body.

Crinolines were relatively inexpensive, so women of all classes eventually adopted them (although the massive yards of fabric needed for truly huge skirts would be a fashion statement only very wealthy women could afford).

The shape crinolines created was so popular that reports were 200 pound of product was lost in the Staffordshire potteries in 1863 due to the wide skirts of working women accidentally sweeping shelves clean.

If you're interested in fashion history (or just really like all of the pretty pictures of dresses I've shown), join my Facebook group Really Old Frocks and follow my @reallyoldfrocks Instagram for more beautiful old-fashioned fashion.

And last but not least, I'm giving away two huge prize packs to celebrate The Governess Was Wicked thanks to a little help from my author friends. You could win ebooks, signed paperbacks, audiobooks, and an Amazon gift card!. All you have to do is enter here:

BONUS: I had to include this stereoscopic picture I ran across in doing my research for this article. It's both creepy and flirtatious with the older gentleman kissing the hand of a young woman who is fending him off coquettishly with her fan.

This Sunday was Marathon Day here in NYC. I, like many New Yorkers, live right near the route. While I love the marathon, sometimes the crowds can get a little rough. This year I cheered on some of the runners earlier in the day and then left the neighborhood to do something I never do. Dear Reader, I went to the Met on a Sunday and took a boatload of photographs.

This Sunday was Marathon Day here in NYC. I, like many New Yorkers, live right near the route. While I love the marathon, sometimes the crowds can get a little rough. This year I cheered on some of the runners earlier in the day and then left the neighborhood to do something I never do. Dear Reader, I went to the Met on a Sunday and took a boatload of photographs.